Roman glass, 1st century AD.

Iridescent amber, translucent blues and greens, pale aubergines – the colors and qualities that define ancient glass are at once elemental and mystical. Legend has it that the secret to glassmaking was discovered, perhaps by accident, in the 3rd century BC on the banks of Belus, a river in the Syrian region of Phoenicia. From its origins in Mesopotamia and its further development under the New Kingdom in Egypt to its refinement during the Roman and Byzantine Empires, glassmaking in the Levant evolved through experimentation and innovation.

Glass fashioned into beads and pendants, Etruscan, 5th Century BC.

Glass of the ancient period was fashioned into beads emulating the effect of semiprecious stones, inlayed into decorative surfaces, and crafted into vessels of many shapes and forms. Archaeological excavations place the first glass objects in the Middle East and Egypt, and later off the coast of Syria and Lebanon. Virtually all of the glass up until the 1st century AD was made using the core-forming technique, a laborious process that involved shaping the body of a vessel around a core, winding colored trails, and adding handles and a rim.

Hellenistic and Roman Periods: The Pinnacle of Ancient Glass

Glassmaking continued to flourish under the incoming civilizations of the Eastern Mediterranean, including the Hellenistic and Roman. The demand for luxury objects surged after Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Near East in the mid 3rd century, and glass was increasingly used as tableware in court settings. Carved decorations in transparent glass of blues, greens, and yellows, as well as mosaic glass began to appear as refined drinking goblets and tableware. However, it wasn't until the solidification of the Roman Empire that the art of glassmaking was truly transformed.

Roman opaque glass, 1st Century AD.

The invention of glass blowing in the 1st century AD revolutionized the craft, allowing ancient glassmakers to expand their virtuosity. For this method, glass is taken from a furnace at the end of a hollow metal pipe, and the artisan blows into the open end, expanding the glass into a bubble. While the glass is still hot, it can be manipulated to produce a range of shapes and color effects, to which tooled decoration can be applied. A refinement in the process of free-blowing glass was the introduction of mold-blowing. For this, the artisan would inflate hot glass into a multi-part mold which could then be opened and removed, allowing for relief decoration. The mold could then be reassembled for reuse.

Surviving free-blown and mold-blown glass of the Roman Imperial Period are unmatched in the beauty and sculptural quality of their organic forms; they set the standards that modern glassmakers still look to today. The Byzantine era was ushered in with the shift of Roman power to the East, and the establishment of its new capital in Constantinople in the 4th century AD. Workshops during this period continued to develop along the shores of the Eastern Mediterranean in cities like Tyre and Sidon.

Translucent blue bowl, Roman, 1st century AD.

Deep purple glass amphora, Roman, 1st Century AD.

The Advent of Islam and a New Era in Glassmaking

By the time of the Arab conquest in the 7th century AD, glassmaking throughout the Levant had already thrived, combining technical skill with beauty, for more than two thousand years. Islamic glassmakers owed a great deal to their forebears in the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, building upon the methods of earlier times such as glass blowing and mold making.

The legacy of Islamic glassmaking – engraved, relief-cut, and enamel-painted glass – was crystallized over several centuries and under different dynasties and Empires, from the early Sasanians in Iran and the Ayyubid and Abbasids in Iraq/Syria, to the Mamluks in Egypt and the Ottomans in modern day Turkey.

From the early Islamic period (7- 9th century), we find glass reminiscent of the Roman imperial repertoire, using incised techniques, as well as sunken honeycomb and hexagonal patterns in transparent yellow-greens and deep blues.

Goblet incised with kufic calligraphy, reading “ "Drink! Blessings from God to the owner of the goblet". Iraq or Syria, 8th Century.

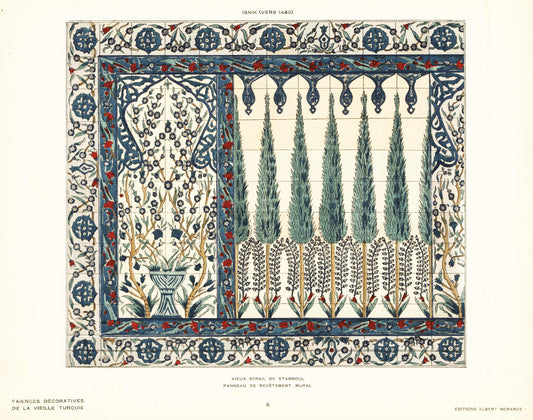

During the medieval period (11-13th century), Mamluk artisans in Egypt mastered the art of enameling and gilding glass, which they used to decorate, among other things, large and impressive glass lamps. We find these enameled lamps hanging in the prayer niches of mosques, above tombs, or in the archways of monumental buildings across Cairo. Interestingly, these lamps became popular export items to Europe where they inspired the early Venetian glassmakers of the 14th century.

Mosque Lamp of Sultan Barquq, Egypt, 1382.

Blank mosque lamps were exported from Venice to the Levant in the 14th century, for final enamel decoration to be executed in the East.

Blank mosque lamps were exported from Venice to the Levant in the 14th century, for final enamel decoration to be executed in the East.

High-quality glass continued to be produced under the great Empires of the Safavids, the Mughals, and the Ottomans, however by the end of the 14th century Islamic glassmaking was already in decline. During the Ottoman Empire, the Levant came into increasing contact with the European West through trade, merchant travel, and diplomatic relations. The accompanying exchange of goods and artistic ideas, particularly between the court of Istanbul and the Serenissima, meant that Venetian artisans gained access to the raw materials needed to produce glass. By the middle of the 14th century, a fundamental shift had occurred: Venice became the leading manufacturer of fine glass. The glass trade, which once flowed from the East across the Mediterranean to the ports of Venice, now reversed course, traveling West to East.

The Legacy of Ottoman Glassmaking

LEVANT's Vesper Glass in blue, modeled after a 12th century Syrian beaker.

LEVANT's 'S' Glass, inspired by an early Islamic glass form.

In the waning years of the Ottoman Empire, in an effort to manufacture decorative glass that was now being imported from Europe, a small hilltop town on the Asian side of Istanbul began to earn a reputation for its glassmaking. Several factories and ateliers were established in Beykoz, some of which survive to this day. LEVANT’s glassware collection is produced by one such artisan in Karlitepe, Beykoz (meaning snowy hilltop) who employs age-old techniques – hand blowing and mold blowing – to craft pieces that evoke ancient forms and honor the glassmaking traditions of civilizations past.

The Vesper Glass in white.

The Vesper Glass in blue.