Like so many of the craft techniques from the Eastern Mediterranean basin, origin stories and precise timelines are murky - often blending fact and legend. Names recorded for these techniques take on a “telephone game” effect; A Turkish word becomes abbreviated in a Syrian city, it transforms into another word entirely in Egypt, and travels back to Turkey in its new form. The craft itself iterates in the hands of artisans from region to region, taking on different motifs or manipulations depending on local tastes, trade culture, and access to raw materials.

The art of tarq’ silver embroidery is one such elusive craft tradition that captivated the Ottoman world and, later, Europe and the West with its resurgence during the Art Deco period of the 1920’s. View LEVANT's Tarq collection.

Precious Embroidery in the East

A 19th Century Ottoman waistcoat, embroidered with gold wrapped thread.

Ottoman waistcoat, back detail.

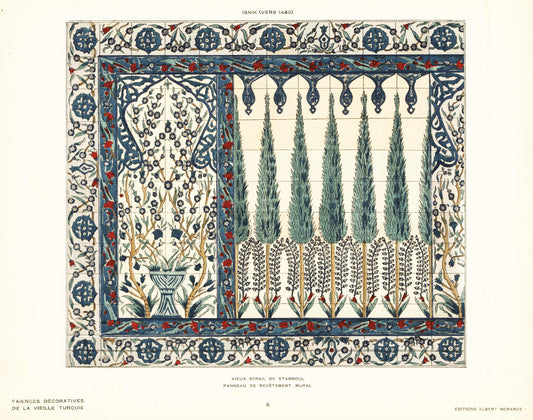

Throughout the Ottoman Empire’s territories, and on the reaches of the Silk Road from Persia to India, embroidery with precious metals was in vogue in various forms for centuries. In the Ottoman courts, sarma was used for opulent waist coats, religious banners, table adornments, and velvet shoes; its origins are purportedly from Damascus, a city with a rich history of textile design ( the word for damask silk comes from the ancient city’s name). In Persia and India, we find zardozi (in Persian zar means gold, dozi - embroidery), that also incorporates pearls and stone embellishment. These techniques created a thick embroidery over fine fabrics, often in floral motifs. It is considered a type of “couch work” embroidery - meaning that the embroidered thread lays on top of the main fabric.

An Ottoman noble circa 1660, in textiles embroidered in gold and silvers, as would have been typical of the period. Engraving by Jacob Gole.

Ottoman 'couchwork' embroidery with silver and silk threads.

Silver tarq’ embroidery on the other hand could be considered a brocade embroidery technique; the silver or gold thread, in flat form, becomes incorporated into the weave of the fabric. The metals used for these embroideries are hammered flat and woven into the textile in geometric forms. The gold or silver is then hammered or tapped into the textile; sometimes with a wooden mallet, other times rolled with a round object.

The Mysterious Art of Tarq'

LEVANT refers to this flat silver embroidery technique as tarq’, a word used by artisans in Baalbek, Lebanon, coming from an old Arabic word meaning ‘to hammer or tap’. Other names for this technique are tally in Egypt, and tel-kirma in Turkey. Some researchers believe the etymology for these names comes from the Turkish word tel, meaning wire. Others have reported that the technique is rooted in Egypt, and the word comes from the Arabic tala’, meaning ‘to coat or paint’.

While the technique was certainly used throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, from Turkey to Lebanon to Egypt, most surviving examples of the technique have Egyptian origins and were produced in the 19th century. Legend reports that Tutankhamun’s tomb had examples of tarq’ embroidery buried within its iconic chambers, though these artifacts are not currently in circulation or documented.

LEVANT's tarq' silver embroidered Palmyra Sky Napkin.

LEVANT's tarq' silver embroidered Palmyra Sky Tablecloth.

One possibility of its origin is that Egyptian artisans used Turkish tel silver and gold, originally used for the popular sarma technique, and invented a new manipulation of the material. In the early 20th century, Egypt saw vast tourism from Europe, due to interest in newly explored archeological sites in Cairo and Karnak. Tarq’ fabrics became a precious exported product, created for the well-to-do visitors who would bring back silver and gold embroidered gauze shawls to Paris, Rome, and London.

Tarq' shawl made in Egypt circa 1920 for the European export market.

Tarq' Shawl made in Egypt from the textile collection of Morris de Camp Crawford, editor of Women's Wear Daily from 1915-1949.

Due to the nature of the tarq’ technique, motifs are nearly always geometric. With the gold and silver, and use of triangular and hard shapes, the craft played well with the aesthetics of Egyptomania and Art Deco. Flapper dresses in tarq’ style were being made in Paris; there are examples of tarq’ embroidery in the textile library of Madeleine Vionnet’s French atelier, sourced from Egypt.

American Hollywood too had interest in glittery tarq’. In the 1949 film ‘Samson and Delilah’ a glamorous Hedy Lamarr is seen draped in a tarq’ creation. In the 1976 film ‘A Star is Born’ Barbara Streisand wears a shimmering tarq’ ensemble, inspired by Art Deco pieces the actress had in her collection. She went on to wear the very same dress to the Grammy Awards in 1977.

Hedy Lamarr in a tarq' embroidered ensemble in the Hollywood film Samson and Delilah, 1949.

Egyptian actress Tahiya Carioka in a tarq' creation, circa 1960.

Hayat Rifaii, master tarq' artisan, in Baalbek, Lebanon.

Tarq’ craft is a disappearing art form in the Eastern Mediterranean, with few ateliers left in Egypt and Turkey, and less that employ the technique in its traditional brocade weave format. In Baalbek, Lebanon the Rifai family has been working with the craft for 120 years, passed down generationally.

Silver is woven and then hammered into textiles.

Hayat Rifai's tarq' students at work.

Hayat Rifai, the family matriarch and grand master of tarq’ craft was taught the technique by her aunts, who in turn learned this technique from a Turkish artisan during the last days of Ottoman rule. In 1998, Hayat was awarded the UNESCO title of ‘Living World Heritage’, for her efforts to preserve this art form. Today Hayat, with her daughters Nidal and Mirvat, operate a small women’s cooperative in Baalbek, teaching this technique to a new generation of women.

The Palmyra Sky Napkin, with silver embroidery on tobacco linen.

The Palmyra Sky Tablecloth, silver on white linen.

Palmyra Sky Tablecloth with Bedouin motif detail.

Wildly intricate, while creating a refined but decadent look on textile, LEVANT has produced a small collection of tarq’ creations on Belgian linens. Works of art set on a table, the silver flecks feel celestial by candlelight - on dreamy white or smoky tobacco brown. An ode to the craft and the city of Baalbek, the pieces speak to the blended traditions and designs of the Eastern Mediterranean, with overlapping references from Palestinian and Bedouin motifs, to Egyptian geometries seen on the art-deco tarq’ pieces of the 1920’s.