Historically referring to the lands on the shores of the Eastern Mediterranean. Stretching from the sea to the Arabian Desert, and from the Taurus mountains in Asia Minor to the Sinai Desert in the south.

The contemporary Levant consists of Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, Israel, Cyprus and Egypt.

Borrowed from the French word levant ‘rising’, or the ‘rising sun in the east’, the verbiage came into popularity during the Franco-Ottoman alliance, established in 1536. This alliance was called the ‘Union of the Lily and the Crescent’, and lasted 250 years.

The result of this trade and military coalition was the creation of thriving cosmopolitan centers in the Ottoman-controlled Mediterranean, where religions, customs, and manners intermingled and exchanged. At times in these cities, there were no clear majorities - Christians, Muslims, Europeans or Turks. As is true to diverse urban centers, harmony also came with periods of sectarian tension. The Levant was an experiment in co-existence that had few parallels to any other state in the world.

Churches and mosques were erected simultaneously in the cities of Smyrna, Alexandria, and Beirut. In bustling Levantine markets, flowing Ottoman robes rubbed shoulders with the European fashions of the day - turbans and powdered wigs, kaftans and broad lace collars. Merry makers danced à la greque, à la français, and à la turque in tavernas and on port jetties. Lingua Franca was the widely spoken language of commerce and revelry - a sort of ‘simple Italian’ without tenses - due to the Ottoman presence in Venice. European embassies were established in the vineyards of Pera in Constantinople, where counts and muftis mingled at fêtes thrown by both Ottoman and Occidental dignitaries and intellectuals.

In bustling Levantine markets, flowing Ottoman robes rubbed shoulders with the European fashions of the day - turbans and powdered wigs, kaftans and broad lace collars.

Dutch Ambassador Cornelis Calkoen at his Audience with Sultan Ahmed III. Painting by Jean Babtiste Vanmour, 1720.

The Levant is where Europe met Asia. A writer of the time notes that the women in the port of Smyrna combine “the grace of the Italians, the vivacity of the Greeks, and the ‘stately tournure’ of the Ottomans, possessing an almost irresistible fascination”. So could be said of the region.

The history of Europeans lured by the charms of the Orient is widely discussed and often criticized due to the West’s imperial ambitions, the theft of artifacts, and caricature of Eastern cultures. Lesser known is the ease of travel and accessibility for tourism created by flexible mandates set forth by the Ottoman Empire. Levantine sites became fashionable destinations, better known than many in Europe.

Syrian men move a column plinth on the site of Tadmor, Syria.

Temples of Palmyra, Syria.

The Temples of Karnak, Egypt.

The archeological masterpieces of the Levant - the temples of Palmyra in Syria, Baalbek in Lebanon, Ephesus in Turkey - were studied and documented by European explorers before the great temples of Paestum, south of Naples, or Diocletian’s Palace on the Dalmatian coast. Adventure tourism started here; the Levant was a land for the curious. Travelers’ written accounts of Levantine courts, markets, and ancient sites circulated across Europe. Prints of exotic locales were stamped and sold in Paris, London, and Rome - generating an aura of glamor and exoticism.

Market in Damascus, Syria. Photograph by Tim Beddow, 2000.

Man with fez, Istanbul. Photograph by Charles Cushman, circa 1980s.

Palace in the old city of Damascus, Syria. Photograph by Tim Beddow, 2000.

Levant’s pre-Ottoman history also informs the illustrious culture that was nurtured in these dynamic trade cities. The region claims the world's oldest cities - Aleppo, Beirut, Jericho, Byblos. Of Damascus, Syria, Marc Twain wrote:

“She measures time not by days and months and years, but by the empires she has seen rise and prosper and crumble into ruin.[…] she saw these villages grow into mighty cities and amaze the world with their grander - and she has lived to see them desolate, deserted. She saw Greece rise and flourish two thousand years and die. In her old age she saw Rome built; she saw it overshadow the world with its power; she saw it perish.”

Indeed, the Levant witnessed the rise and fall of empires, often playing a strategic role in their ascension and decline. The region was ruled by the Persian Empire, followed by the Greeks led by Alexander the Great, and the Romans until 636 C.E. when Arab armies finally conquered the Levant, making it a part of the Rashidun Caliphate.

The Levant witnessed the rise and fall of empires, often playing a strategic role in their ascension and decline.

Portrait of the Poet Sappho, Izmir, Turkey, 2nd Century A.D. Photograph by Don McCullin.

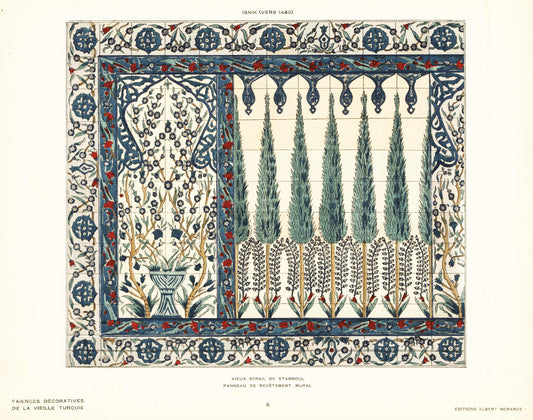

This is the land where Homer was allegedly born, in Turkish Izmir. The Levant is home to the Israelites, Christ and his apostles, and the prophets of Islam. The mix of religions, tribes, and aesthetic and cultural influences brought by trade boats, caravans and army militias is apparent in every corner of the Levant. We find Chinese patterns on mosque walls in Constantinople, a relic of the silk road trade routes. In Afghanistan we find inscriptions in ancient chambers in Greek. On the streets of Palermo we hear Sicilian dialect, a vernacular steeped in the languages of the Mediterranean island’s former occupiers. Sabbinirica, a common greeting in ‘sicilianu’, comes from the Arabic salaam alaikum.

A niche in the Zisa Castle in Palermo, inspired by the Muqurna vaulting in Islamic architecture. The name ‘Zisa’’ comes from the Arabic aziz, meaning ‘dear one’.

The Levant’s intrigue lies in its true collision of culture, the vestiges of its ancient past, and the introduction of Islam that blended with the land’s Mediterranean values.

Spanning countries and centuries, the Levant of today still captures the imagination. From its vast deserts to the beckoning shores of the Mediterranean, an exploration of the Levant is an exploration of civilization itself: the globe’s first true cosmopolitan communities.